Review by MH FRYBURG

You cannot understand American history unless you understand the monumental influence that Abraham Lincoln exerted on American history.

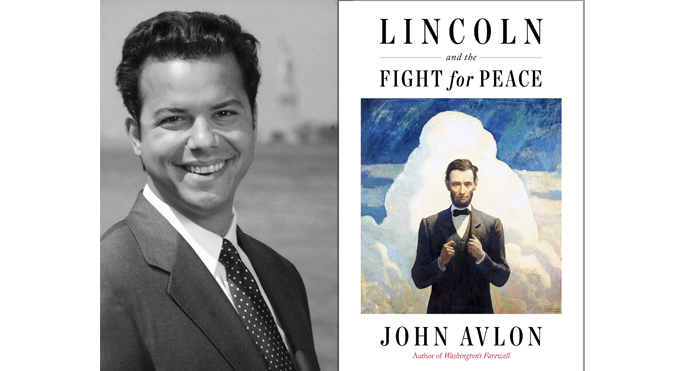

You cannot understand the monumental influence that Abraham Lincoln exerted on American history until you read Lincoln and the Fight for Peace, by John Avlon.

I have long been a big fan of John Avlon’s commentary on CNN, but, until I read Lincoln and the Fight for Peace, I had no idea that Mr. Avlon was as good a writer – and historian – as he is a cable news pundit.

Avlon’s tome focuses on the last 6 weeks of Lincoln’s life, from his 2nd inauguration (on March 4, 1861) until his assassination (on April 14, 1965). Lincoln closed his 2nd inaugural address with a passionate plea for peace, “With malice toward none with charity for all… let us strive on to…do all which may achieve…a just and lasting peace….”

According to Avlon, “Lincoln developed his prescription for peacemaking: unconditional surrender followed by a magnanimous peace.”

On April 9, 1865, General Lee unconditionally surrendered to General Grant, who, applying Lincoln’s policy of a magnanimous peace, acceded to Lee’s request that the Rebel soldiers be allowed to keep their horses, and provided Lee’s troops with desperately needed rations.

Slavery was the central issue in the Civil War; although Abraham Lincoln fiercely opposed slavery, he was not an abolitionist; the Civil War was initially fought to preserve the Union, not to end slavery in the South. The Civil War began with the attack on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, but President Lincoln didn’t issue the Emancipation Proclamation (which stated that “all persons held as slaves” in the areas controlled by the Confederacy “are, and henceforward, shall be free”) until January 1, 1863. The Emancipation Proclamation didn’t actually free anyone when it was issued, but it established, beyond any doubt, that, if the Union won the Civil War, then slavery would be abolished.

One of the most fascinating, and little known facts about American slavery, according to Avlon, was that “Only a small percentage of Southerners actually owned slaves—some 316,000 slave owners out of 5.6 million Southern whites, according to the 1860 census.”

President Lincoln, who was subject to bouts of severe depression, managed to persevere due to the strength of his character. “Lincoln’s leadership style flowed from the essential qualities of his personality: empathy, honest, humor and humility,” Avlon wrote.

According to Avlon:

Lincoln embodied an interpersonal absence of malice. He practiced the politics of the Golden Rule – treating others as he would like to be treated. He did not demonize people he disagreed with…. He was uncommonly honest and tried to depolarize bitter debates by using humor, logic and scripture.

Lincoln’s vision for a magnanimous peace and a quick reintegration of the Confederate states back into the Union died when he did: the hard and bitter peace called “Reconstruction” was imposed by the U.S. Government on the South, causing many Southerners, like Harry Truman’s grandparents (who had been Confederates), to hate and resent the “Yankees.” Lincoln’s plans for peace were dashed and the states of the former Confederacy became the most socially and economically backward part of the United States.

Lincoln’s memory was invoked in appeals to patriotism during WWI, and President Woodrow Wilson, guided by Lincoln’s conception of a magnanimous peace, tried, but failed, to persuade the British and French governments not to impose punitive reparations on Germany. As Avlon explains, WWI ended with a ceasefire (Germany never surrendered unconditionally), which allowed to Hitler and the Nazis to persuade Germans that they didn’t really lose the war, but were betrayed by the Jews and their collaborators.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt was a huge Lincoln fan. On July 3, 1938, speaking on the 75th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg, FDR said that Lincoln understood that the Civil War had to end with the unconditional surrender of the Confederacy so that it would be “accepted as being beyond recall” by the former Rebels.

In 1943, at the Casablanca Conference with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, President Roosevelt announced that the Allies had agreed that Germany and Japan must surrender unconditionally; like Lincoln, FDR realized that unless the German and Japanese people accepted that they had lost the war, there could be no lasting peace.

Militarily, like Lincoln, FDR was a strategic genius; he knew that defeating Germany – rather than Japan — first was the only way to win the war and to create conditions conducive to a lasting peace. That’s why, as Avlon explains, in 1942 the U.S. Government began to plan for the post-war occupation of Germany and Japan.

While focused on winning the war, FDR was also focused on winning the peace; it was FDR who conceived of the United Nations organization, and persuaded Stalin and Churchill to agree that their countries would join the UN.

After WWII ended when Germany and Japan surrendered, unconditionally, President Truman, who was a huge Lincoln fan, applied the Lincoln-Roosevelt policy of a magnanimous peace to the occupation of Germany and Japan. While some Germans and Japanese were tried for war crimes, the “soft” occupations, accompanied by American economic aid, changed Germany and Japan into thriving democracies, and strong American allies.

Avlon ends his book with this trenchant observation:

Lincoln’s example offers us a path away from polarization. His commitment to reconciliation retains the force of revelation. Even during the Civil War, he refused to back down from his belief that there is more that unites us than divides us.

As John Avlon demonstrates, in his must-read book, Lincoln is a paradigm of how leaders should act, and an exemplar of the fundamental American values: truth, freedom, fairness and gratitude.