November 2020

Turkeys and Other Tick Eating Ground Birds:

The wild turkey is an upland ground bird native to North America and the same species as the domestic turkey. Whether the name derived from the bird originally being imported to Britain in ships coming from Turkey, or simply being introduced to England by Turkish merchants, the name stuck all the way to America. Here, on the east end of Long Island the bird is quickly becoming a nuisance wildlife species due to their growing populations and their decreasing habitat.

After hunting and habitat loss drastically decreased their numbers at the beginning of the 20th century, they made a resounding comeback thanks to game management and conservation efforts. To find the epicenter of the turkeys reintroduction, you don’t have to look much farther than Montauk. In fact, it is widely believed that the entire turkey population on Long Island started with the release of captive born or “trap & transferred” birds in Montauk during the early to mid 1970’s. The total United States population at that time was around 1.3 million birds. Today that number has reached 7 million plus nationwide.

Our eastern wild turkey is a subspecies of five other turkeys including the Osceola, the Rio Grande, Mirriam’s, Gould’s and the South Mexican Wild Turkey, in which the domestic species is derived from. The eastern wild turkey was first named the Forest turkey, but as their range spread to various types of habitat with the aid of deforestation, the forest moniker was dropped. Despite their weight, they are great fliers. They also have good eyesight, but only during the daylight hours. At night, they don’t see very well and must roost high in the tallest trees to avoid nighttime predators. Turkeys do not migrate either, so during the colder blustery months, they seek shelter in tall conifer canopies.

Our eastern wild turkey is a subspecies of five other turkeys including the Osceola, the Rio Grande, Mirriam’s, Gould’s and the South Mexican Wild Turkey, in which the domestic species is derived from. The eastern wild turkey was first named the Forest turkey, but as their range spread to various types of habitat with the aid of deforestation, the forest moniker was dropped. Despite their weight, they are great fliers. They also have good eyesight, but only during the daylight hours. At night, they don’t see very well and must roost high in the tallest trees to avoid nighttime predators. Turkeys do not migrate either, so during the colder blustery months, they seek shelter in tall conifer canopies.

There is a lot of interesting information about the wild turkey. Their uniqueness is often overlooked; for example, turkeys have up to 6000 feathers. In a male, these feathers are colored red, purple, green, copper, bronze, gold, white, brown and gradients in between them all. Males usually also have a tuft of hair growing from the center of their chest called a beard, and a pointed spur on the backs of their legs that is sometimes used for defense. They have red wattles covering their head and neck, which are fleshy caruncles, lumps, fans or bags of skin often seen on a farm rooster and other gallinules. The male turkey has a larger wattle that is elongated and hangs over the beak called a snood. When a male turkey is excited, the snood, wattles, head and neck all become engorged with blood and swell to the point of hiding the eyes and beak. One more interesting fact is that they have many vocalizations from kees to cackles, cutts to yelps, purrs to putts, clucks to whines, and of course the always recognized gobble,which can actually be heard up to a mile away. The males also emit a lower pitched sound that they create by moving air in a sack located in their chest. This sound is called “drumming”. When the air is sharply forced from this sack, it creates another sound called a “spit”. That’s a lot of different sounds from one bird.

There is a lot of interesting information about the wild turkey. Their uniqueness is often overlooked; for example, turkeys have up to 6000 feathers. In a male, these feathers are colored red, purple, green, copper, bronze, gold, white, brown and gradients in between them all. Males usually also have a tuft of hair growing from the center of their chest called a beard, and a pointed spur on the backs of their legs that is sometimes used for defense. They have red wattles covering their head and neck, which are fleshy caruncles, lumps, fans or bags of skin often seen on a farm rooster and other gallinules. The male turkey has a larger wattle that is elongated and hangs over the beak called a snood. When a male turkey is excited, the snood, wattles, head and neck all become engorged with blood and swell to the point of hiding the eyes and beak. One more interesting fact is that they have many vocalizations from kees to cackles, cutts to yelps, purrs to putts, clucks to whines, and of course the always recognized gobble,which can actually be heard up to a mile away. The males also emit a lower pitched sound that they create by moving air in a sack located in their chest. This sound is called “drumming”. When the air is sharply forced from this sack, it creates another sound called a “spit”. That’s a lot of different sounds from one bird.

I could easily write this entire column about the turkey as I’ve just “scratched the surface” (pun intended), but my intention was to talk about all the ground birds that help in the defense against the dreaded blood thirsty and disease carrying tick. Turkeys are omnivores with a favored diet of acorns, berries and even grasses, but they are also one of the most voracious tick predators we have in our country, particularly here on the east end of Long Island. One turkey can eat up to 200 ticks or more each day, and often do during the warmer seasons. That’s 6000 a month or over 12,000 per season, greatly surpassing the Virginia Opossum who consumes up to 5000 ticks per season on average. This is a great example of wildlife benefitting the health of human life, a side of nature we rarely take the time to recognize these days.

So, what other animals are tick predators? Fortunately there are several, but even so, their forces are simply not enough to overcome the tick populations that continually increase each year. Domestic additions such as chickens or Guinea fowl (sometimes called Guinea hens) are great tick and insect eaters, particularly on larger parcels of land or cleared lots or yards, but there are other wild critters out there doing the job just as efficiently.

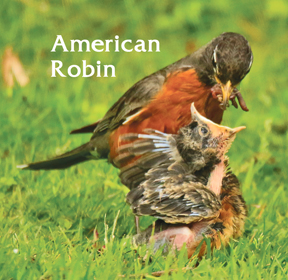

Almost all ground birds, including songbirds that feed generally on the ground, are great tick eaters. The American Robin is one of the all time leading carriers and transporters of the tick, much more than the white tailed deer. In fact, one of the biggest misconceptions is how the deer is the biggest transporter of ticks. This is not true at all folks. The mouse and the Robin, incidentally both a fraction of the size of a deer, are the two main carriers and transporters of the tick. Further more, the deer is immune to the many diseases carried by ticks and it is this author’s opinion that the deer should be studied more for their potential human benefits rather than persecuted for inaccurate, unsubstantiated beliefs or scape coating for decades because of the lack of proper management. My question still remains unanswered; in that, why must the deer be punished by death for the mistakes and continued ignorance of a know-nothing / do-nothing Town administration? Seems to me that when death is the chosen solution to any problem, this means the “powers that be” are either sadistic, have been beaten or just simply given up. Imagine, taking the life of a living thing because you’re too lazy or ignorant to help or work the issue out morally and without killing. Just imagine that for a moment.

Almost all ground birds, including songbirds that feed generally on the ground, are great tick eaters. The American Robin is one of the all time leading carriers and transporters of the tick, much more than the white tailed deer. In fact, one of the biggest misconceptions is how the deer is the biggest transporter of ticks. This is not true at all folks. The mouse and the Robin, incidentally both a fraction of the size of a deer, are the two main carriers and transporters of the tick. Further more, the deer is immune to the many diseases carried by ticks and it is this author’s opinion that the deer should be studied more for their potential human benefits rather than persecuted for inaccurate, unsubstantiated beliefs or scape coating for decades because of the lack of proper management. My question still remains unanswered; in that, why must the deer be punished by death for the mistakes and continued ignorance of a know-nothing / do-nothing Town administration? Seems to me that when death is the chosen solution to any problem, this means the “powers that be” are either sadistic, have been beaten or just simply given up. Imagine, taking the life of a living thing because you’re too lazy or ignorant to help or work the issue out morally and without killing. Just imagine that for a moment.

Here on the east end, we are also fortunate to have a couple other ground birds that love to eat ticks. Both the Ring Necked Pheasant and the Bobwhite Quail once occupied our area in great numbers. Like many species before them, hunting and habitat loss nearly extirpated both animals from the east end. I personally remember as a child growing up in Amagansett during the 60’s and 70’s, the abundance of pheasant throughout East Hampton. And although they were harder to find, the unmistakable call of the Bobwhite quail filled the air in multiples, as each morning broke. Nowadays, the populations of both species are slowly making a comeback on the east end, thanks to hobbyists and organizations dedicated to captive born, farm raising and release, right here locally.

I spoke with an Amagansett resident who was repopulating both quail and pheasant for the specific reason of reducing the tick population. Gene, (who preferred I not use his last name) became tired of all the lip service the Town offered in regards to a tick solution. He told me, “They got so caught up trying to convince the public that the deer was the reason for the ticks, they forgot to address the ticks themselves, or even recognize that the tick was the issue”. Gene, who suffers from Lyme’s Disease, took matters into his own hands and began raising both pheasant and Bobwhite quail to release on his property. He soon realized that between predation and wandering, he would have to replenish his worker birds regularly. It became such an enjoyment, that he soon decided to raise the birds on a larger scale and release them throughout the community in an effort to promote tick relief to the more heavily covered thick or brambled areas.

I recently had the pleasure of rescuing a pair of Bobwhite quails that were a bit domesticated and even more disoriented, following beach goers at one of our local beaches. Now the dunes or beach grass terrain would not be an unusual location to find these birds, but the sandy beach is a bit out of their comfort zone. A little too open, making them very vulnerable to a variety of birds of prey. I brought them home to my yard where it was much safer, and a better starting point for their next journey to finding a proper home, and lots of ticks to eat. So remember folks, our beautiful wildlife is out there doing an important job that not only can benefits humans, but benefits our precious environment as well. And that my friends, is why,…. Wildlife Matters.

See you next month. Until then, gobble gobble!

~ Dell Cullum

Hampton Wildlife: 631-377-6555 · Wildlife Rescue of East Hampton: 844-SAV-WILD

www.WROEH.org · www.ImaginationNature.com